Key Findings

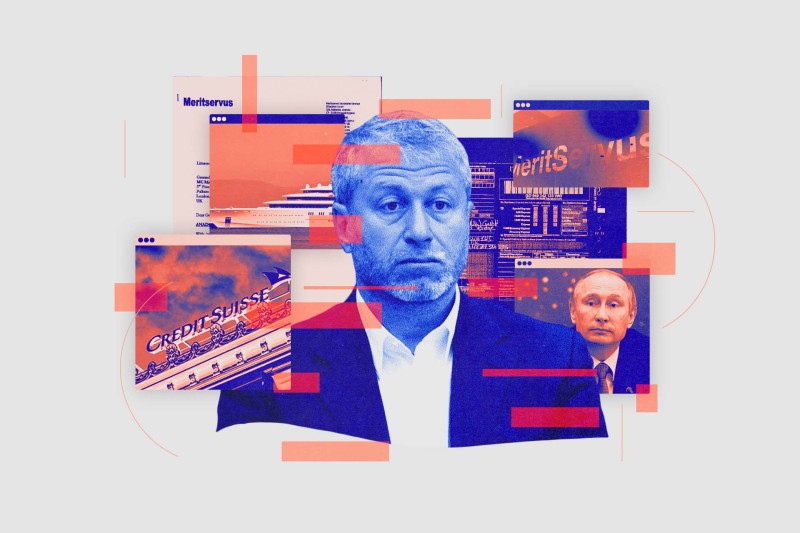

- Leaked documents from Credit Suisse and the Cypriot service provider MeritServus reveal Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich held over two billion in assets or cash across Credit Suisse, UBS and Barclays.

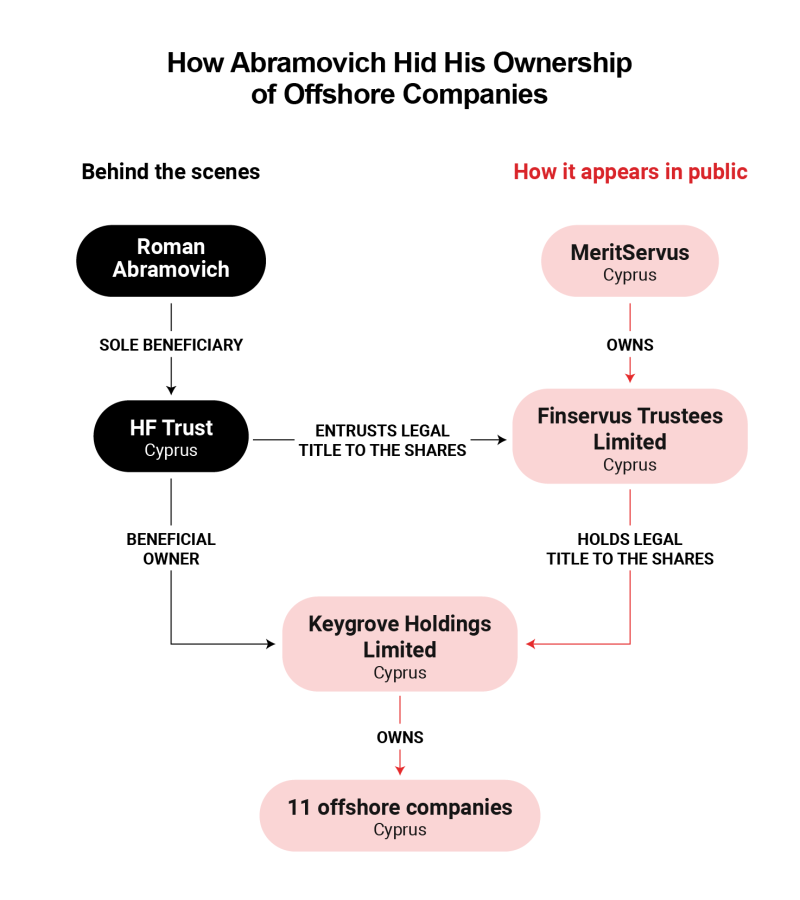

- Abramovich’s ownership of several offshore companies was obscured via a complex corporate structure involving an opaque trust and an intermediary company owned by MeritServus.

- The offshore firms owned blue-chip U.S. stocks which they used as collateral for big loans from Credit Suisse, and engaged in a pattern of mysterious loans between one another that experts said could raise red flags for potential money laundering.

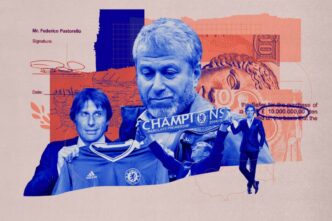

Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, sanctioned by the U.K. and the European Union for his links to Vladimir Putin’s regime, held assets worth over 1.4 billion euros with Credit Suisse through offshore firms that, until recently, he secretly owned.

The companies held stakes worth almost half a billion dollars in two of America’s largest steel companies, and engaged in mystifying loan agreements that experts say raise concerns over their purpose.

The new details on Abramovich’s business empire come from two leaks shared with OCCRP and its partners: documents on Credit Suisse obtained by German start-up Paper Trail Media and a data leak from Cyprus-based corporate service provider MeritServus, released by whistleblower site Distributed Denial of Secrets.

More Suisse Secrets

The Credit Suisse documents were given to Paper Trail Media weeks after the release of last year’s “Suisse Secrets” stories. They show a list of seven previously unknown companies with 1.4 billion euros of assets, all held — according to the source — at the Vienna branch of Credit Suisse Luxembourg. The data shows a snapshot of at least some of Abramovich’s assets at the bank as of 2013, according to the source.

The MeritServus leak confirms the companies in question were owned by Abramovich and registered in Cyprus, and shows several of the firms trading hundreds of millions of euros in assets.

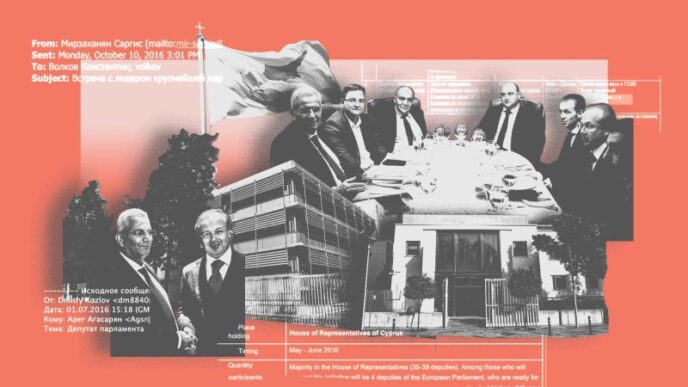

The ownership structure of these companies is labyrinthine, and trusts usually offer an impenetrable wall of anonymity. But the MeritServus leak includes correspondence between MeritServus and banks describing Abramovich as the beneficiary of HF Trust and the companies that sit below its umbrella.

Earlier this month, The Guardian revealed how Abramovich moved the trust into the names of his children weeks before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which led to a wave of sanctions against Russian oligarchs, including Abramovich. While many of the dealings described here relate to the period before sanctions were imposed, Credit Suisse and MeritServus appear to have continued to work with Abramovich’s corporate structures even after Moscow attacked Ukraine.

EU and U.K. laws require banks to freeze assets if they are more than 50-percent owned by a sanctioned individual, or if that person can be shown to have direct or indirect control of the assets.

Neither Credit Suisse nor MeritServus responded to questions about whether they continued to provide services to Abramovich after he was sanctioned.

Justyna Gudzowska from U.S.-based anti-corruption advocacy group The Sentry said U.K. and EU banks should be wary of accepting at face value the transfer of Abramovich’s trusts to his children just before sanctions were imposed.

“The timing of the transfer of the assets to his children should have been a huge red flag for the bank. From a purely legal perspective, there may not be an obligation to freeze, but from a reputational and ongoing risk management standpoint, I would want to get comfort from the relevant sanctions authority and exit that relationship as soon as possible,” she said.

UBS and Barclays, which held at least $940 million of assets for Abramovich’s trust and companies, did not respond to questions from The Guardian about whether they continued to provide services for those entities after Abramovich was sanctioned, but a Barclays representative said the bank “understands the importance of sanctions regulations” and takes its obligations “very seriously.” UBS said it complies “with all relevant sanction requirements.”

Credit Suisse said it “cannot comment on potential client relationships” but that it operates “in strict compliance with all applicable laws, rules and regulations.” The bank has “stringent control mechanisms” to prevent financial crime and ensure all economic sanctions are followed, it said.

Abramovich and his representatives did not respond to repeated requests for comment. MeritServus did not respond to emailed questions from OCCRP, but managing director Demetris Ioannides told OCCRP’s partner The Guardian that MeritServus “has always and will continue to fully comply with all anti-money laundering and sanctions regulations.”

Hidden Ownership

Abramovich appears to have been an important client for MeritServus, a corporate service provider initially established by global auditing firm Deloitte in 1988 that became independent in 2005.

Internal risk-assessment documents drawn up by MeritServus show it played down corruption and money laundering risks, when it came to Abramovich.

In an undated “client risk indicator” form for Abramovich’s company Anadoria Investments Limited, MeritServus said he had “never” been a Politically Exposed Person (PEP), a term used to designate individuals whose political links make them a high risk for bribery and corruption. Abramovich did in fact qualify as a PEP, not just as a billionaire close to Putin but also because of his position as governor of the remote Arctic region of Chukotka from 2000 to 2008, and a lawmaker for the region.

An aerial view of Chukotka.

The same document states that Abramovich’s company was not identified with countries with “significant levels of corruption,” despite Abramovich reportedly admitting in court he made corrupt payments to allow for the rigged purchase of an oil conglomerate in post-Communist Russia, which made him a fortune.

A letter from MeritServus to Credit Suisse sets out the complex corporate structure that served to obscure Abramovich’s ownership of offshore firms. In the letter, Ioannidis, the MeritServus managing director, lists 11 companies that he says are owned by Keygrove Holdings Limited. Ioannidis and his children own Finservus Trustees Limited, which “holds legal title to the shares of Keygrove on behalf of the HF Trust.”

But fundamentally, Ioannidis states, “HF Trust is the ultimate shareholder and beneficial owner” of the offshore companies, and “Abramovich is the sole beneficiary of the HF Trust.”

Abramovich’s companies were structured in a way that obscured his ownership of them behind a Meritservus proxy and HF Trust.

One internal legal opinion from Credit Suisse even confirms that Abramovich did not need to be listed as the designated account holder for HF Trust, keeping his link to its assets at the bank hidden from public scrutiny.

Leaked documents from Credit Suisse offer a snapshot of the assets it managed for Abramovich, listing over 1.4 billion euros, though the precise date of the figures is unclear.

The documents also show how Credit Suisse helped Abramovich turn U.S. stocks into ready cash. A register of charges for Abramovich’s Anadoria — one of many companies held by HF Trust — shows that Credit Suisse loaned his company over $300 million against his shares in United States Steel Corporation and Steel Dynamics, Inc.

Multiple documents show that Deutsche Bank (U.K.) and Citibank (U.K.) provided the same securities-for-loans agreements with Abramovich’s companies, though Deutsche Bank has offboarded Anadoria.

Citibank declined to comment, but Deutsche Bank said it “has no client relationship with Anadoria Investments Limited, and the company has no accounts with Deutsche Bank.”

Besides strategic firms like United States Steel Corporation, Abramovich’s companies owned shares, through various entities, in several blue-chip U.S. companies, including Uber, Microsoft, and Amazon. They also owned shares in UBS and Credit Suisse, including $5.5 million in securities in Credit Suisse’s high-risk bond vehicle, Operational Re III Ltd.

Gudzowska from The Sentry said Abramovich’s access to U.S. financial institutions has likely been severely restricted already, even if he has escaped Treasury Department sanctions.

“Being on the U.K. and EU lists likely significantly hampers his access to the U.S. financial system,” she said. “U.S. banks would generally follow U.K. and EU sanctions as a matter of policy, if not as a matter of law.”

Loan Schemes

One of the most perplexing elements in Abramovich’s offshore dealings are loans between entities that are all owned by him. Experts said such loan arrangements can have legitimate purposes, but can also be used to minimize tax or even launder money.

“Loans without any real rationale can be an effective way of laundering illicit funds through complex networks of companies. If such loans were quickly repaid or used for repeat transactions, as is suggested here, serious questions should be asked about their legitimacy,” said Kush Amin, a lawyer at Transparency International.

A former U.S. government securities fraud officer, speaking anonymously due to professional restrictions in his new job, agreed with Amin, saying such loan arrangements “should raise red flags.”

“Entities like to use these complex schemes to obscure the origin of large amounts of money,” he said.

Details of several mysterious loans emerge in the leaked data. For example, in October 2013, the company Anadoria apparently agreed to receive a $400 million loan from its shareholder Tri-Star Capital Ventures, billed as repayable in October 2023. Like Anadoria, Tri-Star Capital was owned by Abramovich and one of the companies directly banking with Credit Suisse. The company’s annual accounts stated it was under “no obligation” to repay the debt.

Credit Suisse, London.

By January 2018, Anadoria had received another large shareholder loan from Tri-Star Capital Ventures worth just over $315 million, according to the data. The advances were “of no need and serve no purpose,” said the document recording the loan in the corporate records. In total, almost $1 billion apparently was loaned by Abramovich’s parent company to its subsidiary and swiftly returned.

Despite all the loans, Anadoria was consistently in the red, to the tune of over $120 million in some years. The losses do not appear to stem from actual business activity; instead, the company’s annual statements show they seem mainly linked to net losses in the disposal, sale or revaluation of financial assets. In October 2019, the company sold its securities portfolio “to related companies” for $97 million, according to the data. And by 2020 the company exhibited no activity.

Interest-free, no-obligation loans also moved between other Abramovich companies under HF Trust, the data shows. Portland, for example, had received loans worth $600 million by 2017 from Columba, a British Virgin Islands-based company owned by Abramovich that was Portland’s shareholder.

Some of the data’s stated justifications for loans between companies appear dubious. For example, in 2019, Columba loaned Portland another $572.8 million against Portland shares, even though Columba had purchased all of Portland’s shares for $305 million in 2015.

Companies outside the HF Trust portfolio exhibited similar behavior. In 2013 Ovington Worldwide Limited, a British Virgin Islands-registered company owned by Abramovich, loaned over $2.3 billion to another company he owned, Minden, a shareholder of Russia Forestry Products, co-owned by the Kremlin. In 2014, loans worth a similar amount were forgiven and never repaid. Abramovich sold his shares in Russian Forest Products alongside the Kremlin just one month before the Ukraine invasion.