Key Findings

- Russian VTB bank got rid of its shares in Cyprus-based RCB in February, but experts said this did not necessarily mean an end to the ties between RCB and the Kremlin.

- RCB announced in March it would voluntarily cease banking operations, but a banker said European regulators pressured it to stop banking following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- Two opaque Cypriot companies that now own RCB both have ties to RCB officials.

- A leaked Cypriot government report says RCB helped its CEO, Kirill Zimarin, and 31 other staff, their relatives, or bank clients to obtain Cypriot passports under a citizenship-by-investment scheme that was later shown to be corrupt and shut down.

- The report indicates RCB used political influence to push through problematic passport applications, and that many applications associated with the bank did not meet the requirements for Cypriot citizenship.

On March 24, Cyprus’s fourth-largest bank announced it would wind down its banking operations in the wake of the “volatile geopolitical situation” caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a month earlier.

The bank, RCB, had spent years refining an image of itself as a thoroughly European bank, even adopting a logo that mimicked the flag of the European Union and changing its original name, Russian Commercial Bank (Cyprus) Limited, to RCB Bank Ltd. But until the day Russia invaded Ukraine in February, RCB was nearly half-owned by Russia’s VTB Bank, which is closely linked to Vladimir Putin’s government.

Now, Cypriot corporate records and a leaked government document obtained by OCCRP reveal the full extent of RCB’s attempts to disguise its legal ownership and Russian executives as Cypriot. Those attempts became urgent as wide-ranging EU and U.S. sanctions loomed after Russian troops entered Ukraine.

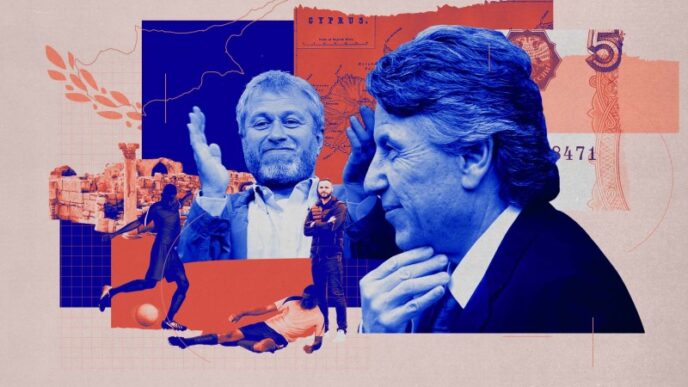

On February 24, RCB announced that VTB’s 46.29-percent stake would be bought by two opaque Cypriot companies that already owned shares in the bank. The move was supposed to distance RCB from Russia, but in fact it was little more than a management buyout.

Although Crendaro Investments Limited, the company that bought most of VTB’s shares, was registered in Cyprus, it is co-owned by the bank’s Russian CEO, Kirill Zimarin, a former VTB manager with ties to the chair of VTB’s management board.

Zimarin, too, is ostensibly Cypriot. He and 31 other RCB staff members and their relatives, as well as some bank clients, obtained passports from the island nation between 2008 and 2019, according to a leaked Cypriot government report obtained by OCCRP. The report, which looked into abuses of the country’s now-defunct citizenship-by-investment scheme, reveals how RCB allegedly helped them do it by hiring a well-connected former Cypriot official who lobbied on their behalf.

They were among 6,700 foreign citizens, including 2,869 Russians, who obtained so-called “golden passports” from Cyprus through the island’s citizenship-by-investment scheme, which allowed foreigners to effectively purchase passports by investing or depositing large sums of money in Cyprus.

When RCB changed its name from Russian Commercial Bank, it said the move was a “logical step” that reflected its “international positioning” and its operations in Cyprus.

But regulators at the European Central Bank have long been concerned about RCB’s links to the Kremlin, according to a European banker familiar with supervisory matters. Even after VTB divested from RCB in February, the Central Bank “thought that because of the bank’s links to VTB and the political situation, it couldn’t continue operating as a viable banking unit,” said the banker, who spoke on condition of anonymity while discussing confidential banking issues.

“It is highly unusual for a profitable bank with hundreds of employees to withdraw from banking and give up its banking license so suddenly,” said James Henry, an economist and longtime investigative journalist focusing on banking. “It’s a clear indication that bank regulators, probably at the [European Central Bank], were concerned that VTB’s role in RCB had been tolerated for too long.”

In its response to OCCRP, RCB strongly rejected “allegations that it has played or is playing any role in any political process” and added that “[t]he only expression of our position throughout the life of RCB has been its absolute rejection of the war and our demand for an immediate end of it.”

From the Kremlin to the Mediterranean

VTB is a Russian state-owned bank that was dubbed Putin’s “piggy bank” after revelations in 2016 from the Panama Papers, a massive leak of corporate records via the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, showing Putin’s allies had used Russian Commercial Bank (Cyprus) to move huge sums of money offshore.

VTB incorporated Russian Commercial Bank (Cyprus) Limited in 1995 to improve its access to Europe and take advantage of Cyprus’s low tax rate, bilateral double taxation agreement, and lack of visa requirements for Russian visitors. After Cyprus adopted the euro in 2008, the bank began opening branches around the Mediterranean nation. The October 2010 inauguration of a branch in Nicosia was even attended by Russia’s president at the time, Dmitry Medvedev, a close ally of Putin. It changed its name to RCB in 2013.

Kremlin connections may have protected RCB from a Cypriot banking crisis that year. European countries sought to push through austerity measures on Cypriot banks that would also have affected depositors at RCB, which had over $17.6 billion in savings at the end of 2012. But Cyprus’s parliament rejected a Eurogroup bailout package after reportedly coming under pressure from Moscow.

The former speaker of the Cypriot parliament said in 2014 that lawmakers had been warned by “the highest Russian leadership” to vote against the Eurogroup deal, according to a report in the Cyprus Mail. In the end a new package was agreed that only affected deposits at Bank of Cyprus and Laiki Bank.

But later, especially after VTB was sanctioned by the EU and U.S. in the aftermath of Russia’s 2014 seizure of the Crimean peninsula, these links became a liability.

When the U.S. sanctioned ten members of VTB’s management board in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it included them among a list of people described as “elites and business executives who are associates and facilitators of the Russian regime”. The sanctions notice added that the VTB executives had “acted or purported to act for or on behalf of, directly or indirectly, the GoR [government of Russia]”.

VTB owned 100 percent of RCB until 2009, when Crendaro Investments Limited acquired 40 percent of the bank. Mitarva Limited, another opaque Cyprus company, picked up 3.81 percent in 2017.

Crendaro is a licenced investment company and fiduciary services provider, which allows it to hold stock in other companies in trust for its clients. Zimarin is the ultimate beneficiary of Crendaro, although on paper half its shares are held by RCB Trustees, another fiduciary company and a subsidiary of RCB.

RCB’s ownership structure changed on February 24, 2022, to make it look more Cypriot. Behind the scenes, the same people were in charge.

Mitarva is owned by two secretive trusts, making it impossible to know who ultimately controls it, though it is reportedly owned by members of RCB’s management.

The remaining 46.29 percent continued to be owned by VTB until these shares, too, were sold to Crendaro and Mitarva in February.

This set-up was possible because Cypriot law allows companies to be owned by trusts and nominee shareholders, keeping the identities of the real owners hidden. Companies are also quick, easy, and cheap to set up on the island via its large industry of lawyers and formation agents. Last year, the transparency campaign group Tax Justice Network ranked Cyprus 14th in the world on its “corporate tax haven index,” ahead of places like Panama, Mauritius and the Isle of Man that are known for corporate secrecy.

Marios Clerides, who chaired the Cyprus Securities and Exchange Commission from 2001 to 2006, said the use of fiduciary services companies as shareholders “makes it very hard for supervisors or regulators to identify the ultimate beneficiaries.” Financial crime lawyer Floris Alexander compared the layers of companies behind RCB to Matryoshka dolls: “Every time you open one, another one will appear”.

The lack of clarity over RCB’s ultimate ownership likely led to problems with the regulator and led to the shutdown of its banking operations a month later, according to finance experts.

“The fact [RCB] has taken these steps suggests very strongly that those [Russian] ties are still both close and hard to disentangle,” said anti-financial crime consultant Graham Barrow.

Henry said it was clear “the ECB wasn’t buying RCB’s claim” that the share transfer meant RCB was no longer “a storefront operation at the beck and call of [VTB].” This meant RCB had only one choice, Henry said: “Get out of banking completely.”

Big-Hitting Russian Bankers

Two prominent Russian bankers, one of whom was sanctioned following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine for his ties to the Kremlin, played key roles at RCB.

Andrey Kostin chaired RCB’s board in the mid-2000s while also serving as the chairman of VTB’s management board since 2002. He is a high-ranking member of Putin’s United Russia party and publicly supported the annexation of Crimea. The EU added Kostin to its sanctions list in February, but he has been under U.S. sanctions since 2018.

A 2019 report into Kremlin-linked corruption by Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny, who is now imprisoned, claimed that RCB CEO Kirill Zimarin gave a Moscow property to Kostin’s girlfriend as a gift.

In an emailed statement, RCB said that “the purchase of [the] flat” was related to a “deeply personal story set in the past.”

The other big-hitting Russian banker is Mikhail Kuzovlev, who was CEO of RCB from 2005 to 2008. Kuzovlev co-founded Crendaro with Zimarin, but passed his 50-percent stake in the company to RCB Trustees (Cyprus) Limited in 2011. Company records show RCB Trustees paid no funds to acquire the shares.

Kuzovlev also has ties to powerful Cypriots: The country’s former president, Demetris Christofias, was reportedly a godfather to Kuzovlev’s children.

Also in 2011, VTB installed Kuzovlev as head of Bank of Moscow, which it had just purchased. The two banks merged five years later. By 2014 Kuzovlev was named third on a list of highest-earning Russian managers. Kostin topped the list.

The ties between the two banks have remained extensive. Financial reports indicate that VTB’s deposits at RCB accounted for 30 percent of RCB’s 4.9-billion-euro balance sheet at the end of 2020.

VTB’s Kremlin links also appear to have filtered down to RCB. In 2016, OCCRP reported that cellist Sergei Roldugin, a close friend and associate of Putin, received $650 million in unsecured loans from RCB. Rodulgin is suspected of being a proxy for Putin.

RCB described the reports at the time as “utterly unfounded.” The bank told OCCRP that “Rodulgin [sic] has never been a client of our Bank, nor have any companies affiliated to him, according to the information disclosed to us, been clients of the Bank.”

“The Bank did not provide unsecured loans and that all loans provided were secured, serviced according to the schedules and repaid in full,” it added.

In December 2017, the Central Bank of Cyprus imposed an 800,000-euro fine on RCB, citing failures in compliance with the island’s anti-money laundering legislation.

Passports, Anyone?

RCB’s Russian ties are a microcosm of the significant presence and influence of Russia in Cyprus, which has been dubbed “Moscow on the Med.” Cyprus is the country that Russia invests most heavily in by far, and vice versa: As of October 2021, Russia’s total foreign direct investment in Cyprus amounted to over $210 billion.

There are no up-to-date official statistics on the number of Russians living in Cyprus, but the figure is widely reported to be at least 40,000 out of a total population of around 1.2 million. A sign in the main port town of Limassol even reads “Limassolgrad” in Russian.

Women talking outside a mini-market selling Russian products in Limassol.

At least 28 Russians linked to RCB joined their countrymen in Cyprus after acquiring passports under the country’s citizenship-by-investment scheme. CEO Zimarin was granted his in 2008, and three other key players at RCB had secured citizenship by 2010.

In October 2020, Cyprus’s government canceled the controversial program, which had been criticized for selling citizenship to criminals, after an undercover investigation by Al Jazeera exposed politicians helping obtain a passport for a fictitious person with a criminal record.

RCB also used political influence to push through problematic passport applications, according to a committee tasked by the Cypriot Attorney General with investigating wrongdoing in the program.

In 2006, Sotirios Zackheos retired as permanent secretary of Cyprus’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the following year he was made a director of RCB. The committee looking into the passport sales found Zackheos played a key role in “coordinating” passport applications submitted by RCB executives and their relatives and “offering clarifications where needed.”

It also said former Interior Minister Constantinos Petrides, now minister of finance, claimed Zackheos and Zimarin met with him to pressure him to approve the application of someone who had been sanctioned in response to the 2014 annexation of Crimea by Russia.

”[They] almost accused me of being a traitor and harming relations between Cyprus and Russia because I didn’t want to naturalize a person.”

Constantinos Petrides

Former Interior Minister of Cyprus

“It was particularly intense to the point where one of them [Zackheos or Zimarin] almost accused me of being a traitor and harming relations between Cyprus and Russia, because I didn’t want to naturalize a person,” Petrides said.

“The gentleman in question went to the presidential office” to complain.

The report did not name the sanctioned individual or give further details, but an annex cited Petrides saying Zimarin had lobbied Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades on behalf of the same person. The committee concluded that the banker exerted “strong influence.”

Zackheos did not respond to a request for comment.

In total, 32 people linked to RCB received Cypriot passports, according to the report, which suggests RCB facilitated this by providing letters attesting that the applicants had the required sum of money on deposit at the bank. In all but one of these cases, the applicants didn’t provide any other proof they had the funds.

Shortcuts to Citizenship

RCB figures appeared to obtain passports while sidestepping some of the requirements of Cyprus’s citizenship-by-investment program, according to the committee looking into the passport sale program.

The committee said RCB’s CEO Zimarin had submitted a certificate signed by a bank colleague attesting to his assets, rather than bank statements to prove he had the required 18 million euros. Zimarin signed a similar certificate to support the application of another RCB colleague, Petr Zaytsev, the committee claimed.

The committee’s report also cast doubt on the legitimacy of the purported deposits of RCB-linked applicants. The committee called on the Cypriot central bank to check the origin of the funds.

The report flagged that Zimarin’s father Alexander also secured a Cypriot passport while he was a recipient of a “modest pension” from Russia that could not have provided the funds required to qualify for citizenship. The committee said it was likely the father’s “deposits did not belong to him but probably to his son.”

Neither ex-CEO Mikhail Kuzovlev nor Zimarin’s father had satisfied the requirement of having a residence in Cyprus at the time their passports were granted, according to the report.

The committee raised a series of other irregularities in the applications of RCB-linked individuals, many relating to the authenticity of their Cypriot residences, the allocation of passports to their family members, the origin of their funds, or the validity of their claims to be connected to Cyprus.

RCB also helped two of its Ukrainian clients with close business ties to Russia obtain Cypriot passports, the leaked Cypriot government report shows.

Makar Paseniuk and his business partner Konstyantyn Stetsenko, who co-founded investment company ICU, had their citizenship applications approved in January 2017. ICU controls over a third of the Russian Burger King franchise’s shares.

The Canada-based owner of Burger King said in March the Russian operator of its outlets had “refused” to shut them down, despite its attempt to cease business in Russia in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine. ICU told OCCRP it had decided to sell its stake in Burger King Russia.