On April 25, Reuters published the full text of the U.S. plan to end the war in Ukraine. The proposed solution envisages the transfer of several Ukrainian regions to Russia. The parliaments of Ukraine, the Czech Republic, France, the UK, and the Baltic states compared the document to the Munich Agreement of 1938, which saw the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia handed over to Nazi Germany without Czechoslovakia’s consent. Another analogous example of non-consensual partition is the 1945 Yalta Conference, which doomed Poland to a place in Eastern Europe’s Soviet zone of influence. Leveraging the lack of unity among the American and British leaders at the time, Joseph Stalin achieved substantial gains. Unsurprisingly, after the war, the Soviet dictator failed to honor his promises to ensure democracy in the lands under Moscow’s domination. Polish historians call the Yalta agreements the “fourth partition,” drawing the parallel with previous instances when the country was split up between empires. As a result, the word “Yalta” is synonymous with betrayal on the part of Western leaders.

Prologue to peace

February 1945. World War II is coming to a close. The Red Army is already fighting on German territory, and the Allies are bracing themselves for a crucial debate on the future of Europe in liberated Crimea. The prologue to the Yalta Conference is the meeting of the U.S. and British leaders in Malta.

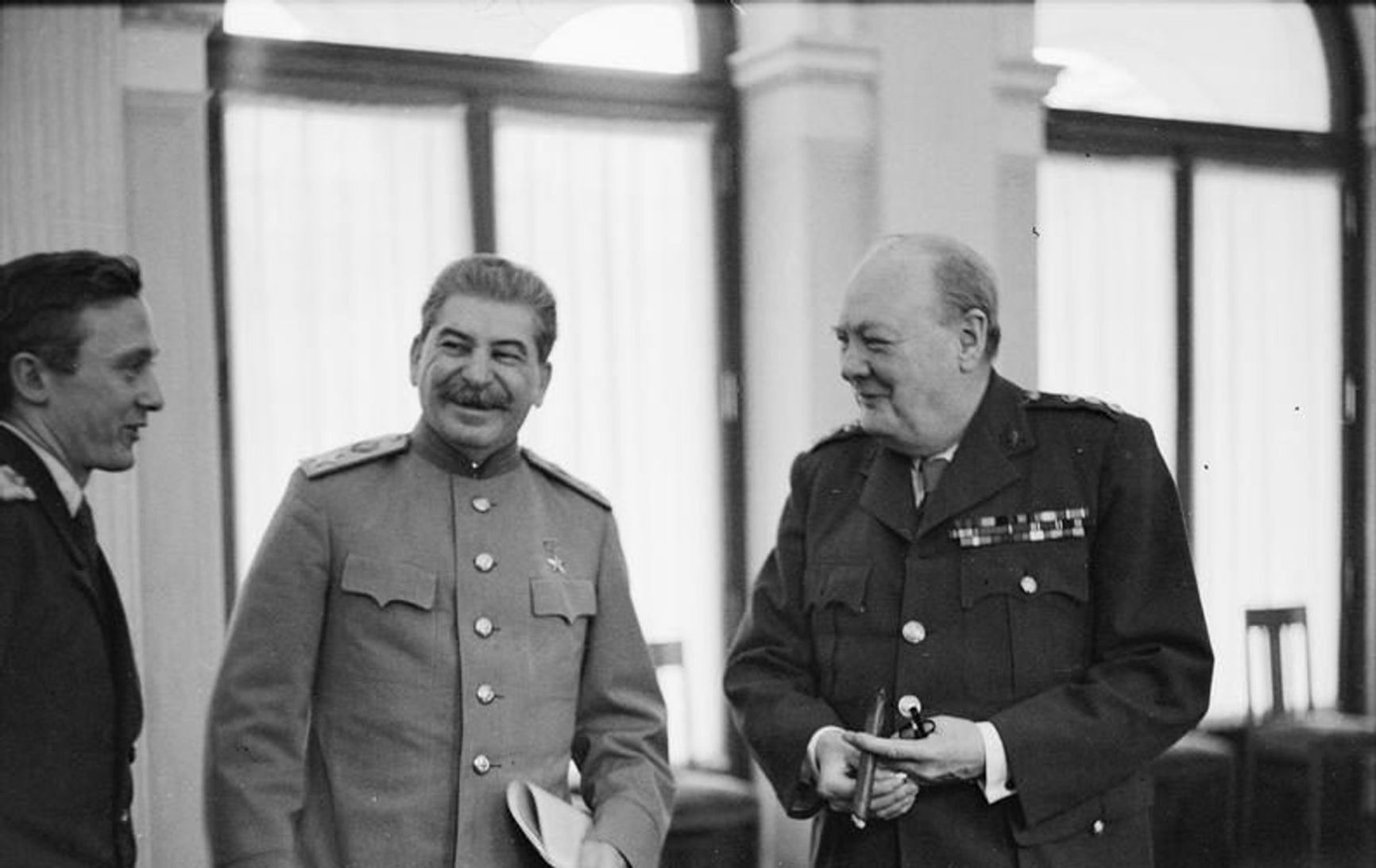

U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt arrived on the island on Feb. 2 aboard the cruiser USS Quincy. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had arrived several days prior, insisted on meeting with the American president before the two sat down for talks with Joseph Stalin. Churchill expressed his concern that unless the Allies agreed among themselves in advance, the Soviet leader could impose his agenda upon them.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

Malta, a symbol of resilience that had survived more than 3,000 air raids during World War II, became the place where the post-war future was decided. British and American leaders discussed the fate of Germany, the borders of Poland, the roles of the Big Three in Europe, and the still-raging war with Japan. The allies agreed that a Red Army advance in Central Europe was undesirable, but agreements had to be reached quickly, as the repartition of the world had already begun.

Controversy and manipulations in Yalta

After the Malta talks, Roosevelt and Churchill traveled to Crimea to meet with Stalin. Although the leaders had agreed to use the conference as a platform to decide the postwar order in Europe, the goals pursued by the Allies varied.

For the British, the key issue remained the fate of Poland. Churchill and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden feared that Moscow would prevent the formation of an independent government in Warsaw and instead entrench a regime loyal to the Kremlin. London needed guarantees that Poland would retain at least formal sovereignty.

Roosevelt, on the other hand, took a broader view of the situation. His main goal was to create the United Nations, a structure capable of preventing future global conflicts. To that end, he was ready to make compromises, including with the Soviet Union. Unlike Churchill, who was suspicious of the USSR, the American president believed that an approach involving trust and openness was the best way to establish a constructive dialogue.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

Unlike Churchill, who was suspicious of the USSR, U.S. President Roosevelt was willing to compromise with Stalin

Stalin, in turn, intended to strengthen Soviet influence in Europe and skillfully exploited the differences between the Western allies to achieve his goal. When Roosevelt proposed establishing a direct connection between General Eisenhower and the highest military command of the USSR, the Soviet leader immediately endorsed the idea. Stalin encouraged the U.S. desire for greater openness, but he gave minimal information in return.

With cautious Churchill, Stalin chose a different tactic. During one of the meetings at the conference, Stalin unexpectedly inquired about the situation in Greece. In October 1944, the leaders of the UK and USSR had secretly settled on a “Percentages agreement” that would determine the influence of each power in a handful of eastern European states. Some historians interpret Stalin’s 1945 interest in Greece — which was slated to remain 90% under Western control — as a hint that Stalin was interested in extending a similar mechanism to Poland and France. Churchill, however, either failed to grasp the message or else simply chose not to respond. As chief of the British General Staff Sir Alan Brooke later noted, the prime minister missed many such signals.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

But Stalin had no intention of easing the pressure. At another meeting, he claimed that Polish partisans had killed 212 Red Army soldiers in the Soviet rear. This allegation forced Churchill and Roosevelt to recognize “the inadmissibility of attacks on the Red Army” by supporters of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), the independent Polish resistance movement. As a consequence, NKVD troops were given the green light to suppress the anti-Soviet opposition inside Poland.

Roosevelt, who was visibly weakened by illness (he would die on Apr. 12, a mere two months after the conference), did not intervene in arguments between Churchill and Stalin. Instead, he simply continued to press for free elections in Poland — a demand doomed to failure in a country where the Soviet command had control over all levers of power. Harry Hopkins, a top adviser to the U.S. president, later recalled that Roosevelt did not seem to grasp at least half of what was happening in the negotiations.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

With all power concentrated in the hands of the Soviet high command, free elections in Poland were doomed to failure

Following the Yalta Conference, the parties adopted the Declaration of Liberated Europe, which proclaimed the right of all peoples of the post-war continent to self-government and the establishment of democratic institutions of their own choosing. The status of Poland was separately stipulated: the pro-Soviet provisional government that had been operating in the country should be transformed into a broader body that would include representatives of all democratic forces, including the government-in-exile associated with the Polish resistance movement.

Poland instead of Greece

The events that followed the Yalta Conference showed that Moscow had no intention of allowing for Poland’s independence. Already in March, the NKVD arrested 16 resistance members who had been guaranteed security in exchange for their agreement to hold talks with the Soviets about their place in the postwar government. The signing of the Treaty of Friendship, Mutual Assistance and Post-War Cooperation by the USSR and the Polish government on Apr. 21, 1945, showed the Allies that “matters with the Polish question had really reached a dead end.”

The treaty essentially cemented Soviet influence over Polish politics for decades. In response to the protests of London and Washington, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov warned that the Soviet side would not tolerate Western interference in Polish affairs. It became obvious that the Kremlin’s interpretation of the agreements was quite different from that of its Western allies.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

Soviet influence on Polish politics was endured for decades

Churchill began to suspect that both he and Roosevelt had fallen prey to subtle diplomatic manipulation. Trust in the Soviet leader had previously been grounded in his non-interference in Greek affairs. But as it turned out, Stalin did not see Greece as strategically valuable.

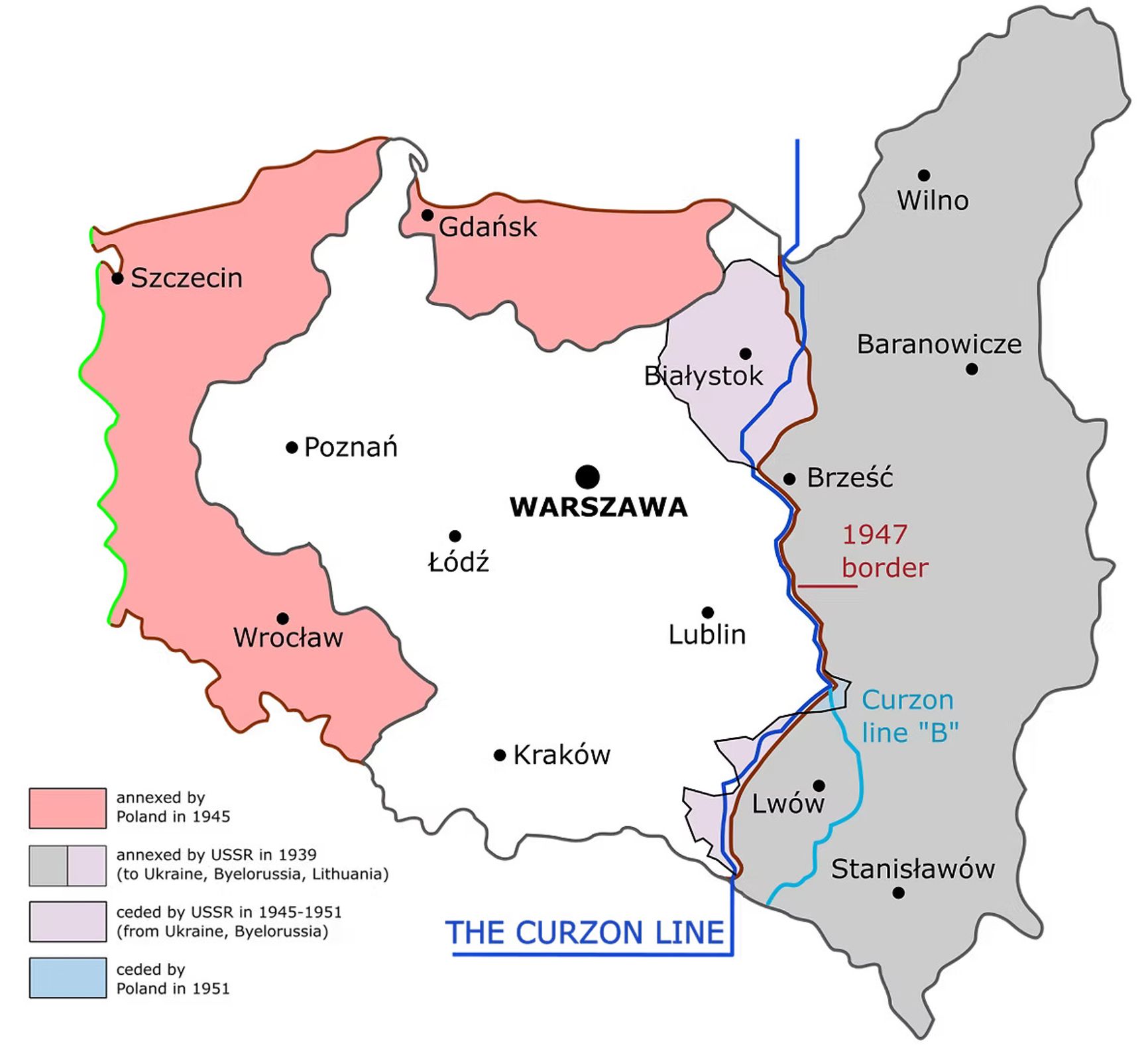

At Yalta, the Allies agreed on the postwar borders of Poland: the eastern frontier was to pass through the Belarusian regions of Grodno and Brest, and Ukraine’s Lviv. As for the western border, Stalin proposed to move it as far as the Oder and the Neisse. The U.S. and UK were reluctant to accept such terms, but at the July conference in Potsdam, they agreed to Stalin’s demands — in no small part due to the fact that Soviet troops had established control over the future Polish territories as early as March.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

The Potsdam Conference concluded the series of negotiations between the Big Three leaders. Its agenda primarily concerned the fate of defeated Germany, determining that the Nazi regime would be completely eliminated, but the USSR, U.S., and UK were in effect deciding the fate of much of the world: how to divide Europe, how to rebuild the destroyed countries, and how to shape an international order that would prevent conflicts of such scale from repeating themselves in the future. No other states affected by World War II were offered a seat at the table.

The price of war

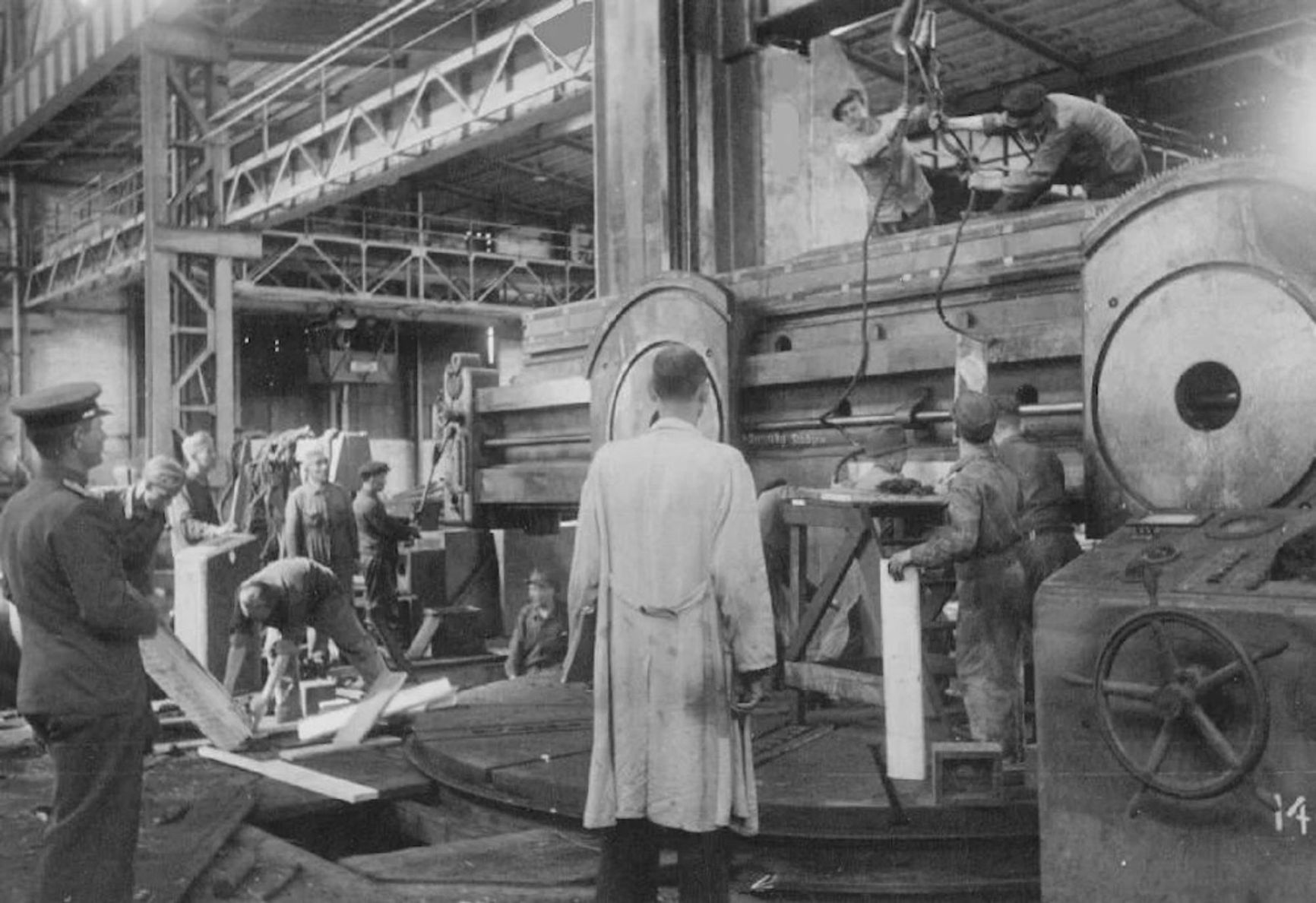

After the war, the Soviet Union formally promoted the industrialization of Eastern Europe. However, it simultaneously demanded war reparations from the states it had “liberated,” thereby putting a further dent in the region’s industry. Anne Applebaum details this process in “Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-56.”

Soviet economists discussed the possible effects of reparations as early as 1943. Yevgeny Varga, head of the Soviet Institute of World Economy and World Politics, warned that these actions could “alienate the working class” in Germany and neighboring countries. Varga advocated for mixed reparations: payments in goods and property, including industrial equipment. He also considered liquidating German enterprises and carrying out an agrarian reform in order to bring the standard of living in line with that of the Soviets.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

Yevgeny Varga, head of the Soviet Institute of World Economy and World Politics, warned that reparations could “alienate the German working class”

These ideas found support at the top levels of the Soviet leadership. Already in Tehran and Yalta, Stalin had announced plans to remove up to 80% of Germany’s industrial equipment. According to him, the USSR was due $10 billion in compensation for damages caused by the war. Churchill warned that harsh sanctions after World War I had destabilized Europe once already, but Roosevelt did not challenge the Soviets’ demands. Moreover, U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. supported the idea of turning Germany into an agrarian country.

But a final decision on reparations was never made, and as a result the Soviets acted on the ground without regard for Allied opinion. By the summer of 1945, 70,000 Soviet specialists had arrived in Germany to handle the export of equipment. According to archival data, 1.28 million tons of materials and 3.6 million tons of equipment were taken out of East Germany before August 1945.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

Plants were dismantled and sent to the USSR. Along with machinery, Soviet specialists removed artworks, archival documents, and even personal belongings from abandoned houses. In the process, complex machines were often disassembled by people without proper training. Predictably, most of the seized assets fell into disrepair.

In reality, the reparations plunged the entire region into ruin. Historians still argue as to whether this reality was dictated by economic expediency or whether it was simply driven by Stalin’s desire to deprive Germany once and for all of any chance of restoring its industrial might.

Economic ruin was not the only problem facing Eastern Europe after World War II. Another thorny issue was mass deportations. The Potsdam Agreement dryly stated that “the German population or part thereof” from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary was to be “transferred to Germany.” However, back in January 1945, six months before the document was even signed, the USSR had already deported 70,000 ethnic Germans from Romania.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

The agreement to shift Poland’s borders to the west also meant a massive population exchange. Ukrainian Poles were to move to Polish territory, and Polish Ukrainians to the USSR. The deportation of Hungarians from Czechoslovakia and Slovaks from Hungary was not officially discussed at all, but when the resettlement began, there was no serious objection from the international community. Formally, the agreements required that “any displacement must take place in an organized and humane manner.” However, the first waves of deportations — those from the Sudetenland, for example — were accompanied by chaos and brutality.

In addition, the German regions slated for Polish control came under the jurisdiction of the NKVD. Repressions here were no less severe than in other Soviet-occupied areas, and in some places they even exceeded them in scale. NKVD General Nikolay Selivanovsky was appointed as an advisor to the Polish Ministry of Public Security, and the Soviets quickly established total control in the country, leaving the Poles no chance for independence.

Mistake or betrayal?

As early as March 1945, Churchill recognized in private correspondence that the West had failed to prevent the USSR from seizing control of Poland. As Roosevelt later admitted, “We can’t do business with Stalin. He has broken every one of the promises he made at Yalta.”

Poland itself perceived the outcome of the Yalta Conference as a betrayal. The agreements are called the “fourth partition,” an allusion to the fact that the country had been divided up between neighboring empires on several occasions since the 18th century. Andrzej Friszke, one of the most respected scholars of Poland’s modern history, says the partition was “informal but no less painful than the previous ones.”

“The term ‘fourth partition’ reflects the collective trauma of the Poles — the feeling that the great powers betrayed them again in 1945,” explained Wlodzimierz Borodziej, an international relations expert and co-author of German-Polish history textbooks, to the Polish publication Tygodnik Powszechny in 2015.

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.

The term “fourth partition” reflects the collective trauma of the Poles — the feeling that the great powers betrayed them again in 1945

Even those researchers who avoid such emotional language recognize that Yalta cemented Poland’s dependence on the USSR — and that it did so with the tacit consent of the West. As Pawel Machcewicz, the founder of the World War II Museum in Gdansk, wrote: “For Poles, Yalta is a symbol of helplessness. The Allies sacrificed us for the big game.”

Paweł Machcewicz. Polska pamięć. O wojnie i okupacji (2017), s. 112.

Andrzej Friszke. Polska. Losy państwa i narodu 1939–1989 (Warszawa, 2003), s. 187.

Martin Gilbert. Churchill: A Life.

Sherwood Robert E. The White House Papers of Harry L. Hopkins.

Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939–1945: Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke.