Rising tensions between the U.S. and Iran — and the looming threat of a new war that could topple the ayatollahs — have once again thrust America’s role as an agent of democracy promotion back into the global spotlight. While Washington’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq tarnished the idea that dictatorial regimes can be successfully replaced via military intervention, the notion of a special mission to advance democracy and freedom has been a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy since the 19th century. Americans have long seen their country not just as a state but as a model for others and a guarantor of the global order, and this worldview only solidified after World War II and saw renewed momentum following the attacks of September 11, 2001. But while the U.S. played a crucial role in fostering modern democratic systems in Germany, Japan, and South Korea, the outcomes of 21st century interventions have been far less successful. Experience shows that military intervention without a carefully crafted plan for state-building only leads to chaos and devastation.

Contents

From plantations to protectorates

The idea of American exceptionalism, rooted in the very foundation of the country’s republican tradition, has guided U.S. foreign policy for centuries. As historian Ivan Kurilla writes in his book Americans and Everyone Else, missionary zeal was a core part of American identity long before the United States became a global power. Americans viewed their political system not merely as a national choice but as a universal model that could and should be exported. Over time, this conviction evolved into a form of moral justification for foreign intervention: bringing American values to others meant bringing “freedom.”

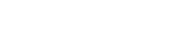

The practice of U.S. interference in other nations’ internal affairs began at the end of the 19th century. One of the first such episodes was the overthrow of the Hawaiian government in 1893. The Hawaiian Islands were of significant economic importance thanks not only to their strategic location, but to their sugar plantations. American businessmen, who controlled the plantations, played a dominant role in the local economy and gradually expanded their political influence. When Queen Liliʻuokalani attempted to carry out reforms that would return power to the native population, it sparked fierce opposition from the Americans.

Businessmen quickly organized a conspiracy against the queen, securing the support of the official U.S. representative in Hawaii, diplomat John Stevens. Citing the need to protect the lives and property of American citizens, Stevens authorized the landing of a detachment of U.S. Marines on the islands. The American military presence ensured the success of the coup: the queen was deposed, and power passed to a provisional government made up entirely of supporters of annexation by the United States, a process that was officially completed in 1898.

The Hawaii episode illustrates the fact that rhetoric around protecting freedom and guaranteeing peace often masked more pragmatic goals — namely, defending business interests and strategic influence.

Behind the rhetoric of defending freedom and the interests of American citizens often lay more pragmatic goals — protecting business and strategic influence

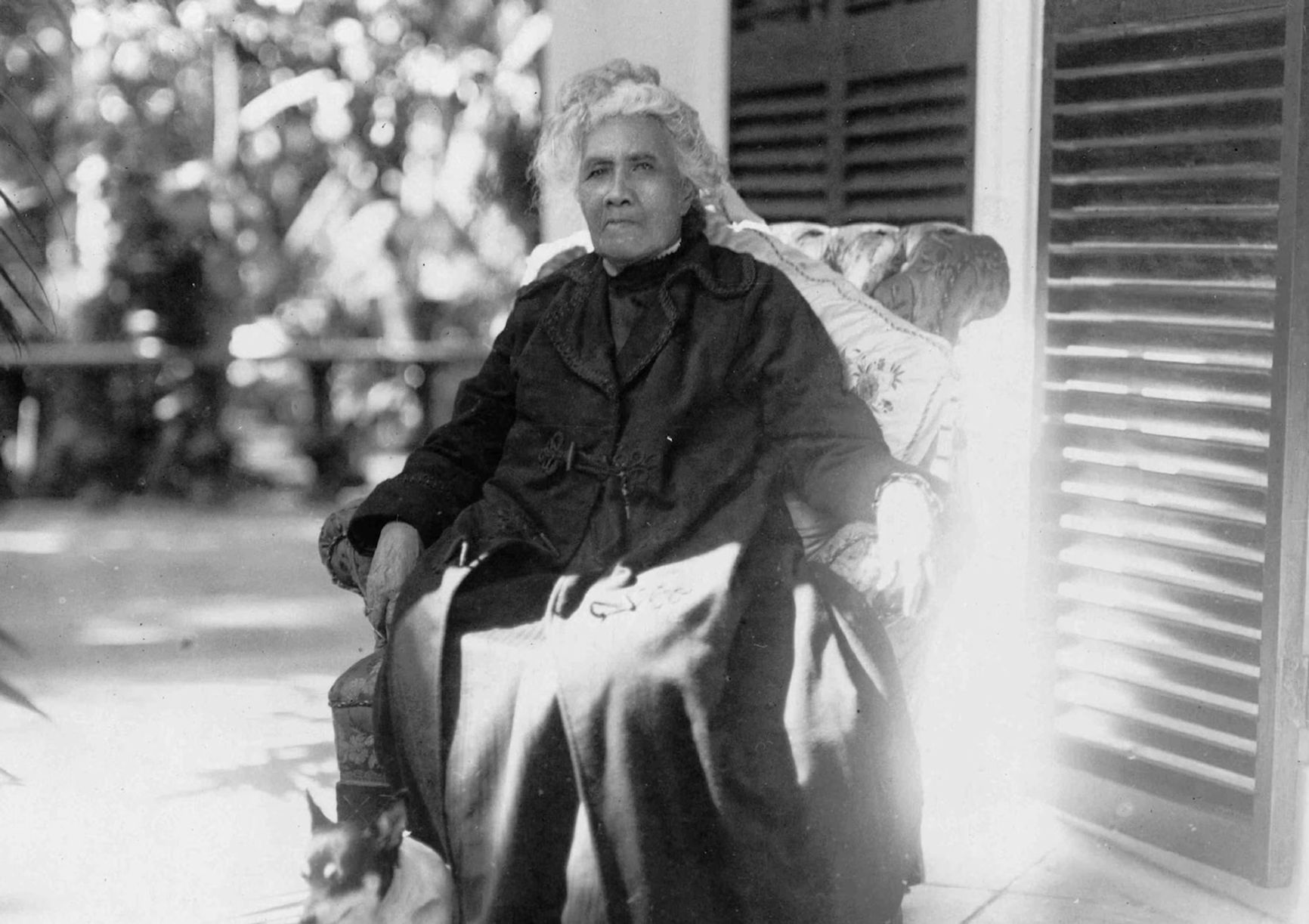

The year 1898 also saw the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, which would define the course of U.S. foreign policy for decades to come. The pretext was Cuba’s struggle to free itself from longstanding Spanish colonial rule. The United States publicly supported the Cuban cause, declared war on Spain, and cast itself as a liberator of peoples suffering under imperial oppression.

American forces quickly defeated the Spanish military, but instead of granting Cuba full independence, the U.S. established what was effectively a protectorate. The Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico also came under American control, significantly expanding Washington’s global strategic and economic influence. In the end, the declarations of support for freedom and independence served as a pretext for expanding territorial and economic reach.

The first half of the 20th century was marked by active U.S. interference in the affairs of Central American and Caribbean states. American companies had significant economic interests in the region — building the Panama Canal, and growing fruit (primarily bananas) — but political instability and internal conflict stood in the way of realizing these interests.

One of the most prominent examples of such intervention was the long occupation of Haiti. U.S. troops occupied the country from 1915 to 1934, taking full control of its financial system and political administration. The pretext for the invasion was “the need to ensure stability and protect foreign investments,” but in reality the American administration governed the country without regard for the interests of the local population. This sparked a powerful wave of resentment among Haitians, who saw the American presence as an example of colonial aggression.

Under the pretext of “ensuring stability,” Americans effectively ruled Haiti with no regard for the interests of the local population

A similar situation unfolded in Nicaragua in the 1920s. U.S. troops intervened in the country’s internal conflicts, backing political leaders who were willing to advance American business and geopolitical interests. As a result of this policy, the United States came to be seen throughout Central America not as a defender of freedom, but as an aggressor concerned only with its own economic gain.

Marshall Plan allies

After World War II, the world was split into two opposing blocs: the capitalist one, led by the United States, and the socialist one, led by the Soviet Union. In this new context, American foreign policy took on a broader scope, and a new objective — to contain the spread of communism and strengthen U.S. global influence. U.S. leaders concluded that the best way to ensure stability and prevent future conflicts was to radically restructure the political and economic systems of defeated nations so that they would become reliable allies and support American interests.

After World War II, American foreign policy acquired a new mission: to counter the spread of communism

The clearest examples of this policy were the occupation and subsequent reconstruction of Germany and Japan. Both countries had been thoroughly defeated in the war, their former political regimes had been dismantled, and their economies were left in ruins. In Japan, the American occupation administration, led by General Douglas MacArthur, carried out sweeping political and economic reforms. Emperor Hirohito formally remained on the throne, but his power was drastically curtailed by a new democratic constitution.

The constitution introduced by the Americans guaranteed civil rights and liberties, restricted Japan’s ability to maintain its own military, and laid the foundations for parliamentary democracy. At the same time, the U.S. invested heavily in rebuilding Japan’s economy, enabling the country to recover quickly from the war and to become a reliable U.S. partner in Asia.

A similar process unfolded in postwar Germany, which was divided into four occupation zones — American, British, French, and Soviet — before the three Western-administered areas united in 1949 to form the Federal Republic of Germany, better known as West Germany. The Marshall Plan played a key role in the recovery of West Germany, where American influence actively supported the creation of democratic institutions and political parties aligned with the Western model of development.

However, reconstruction took place against the backdrop of growing tensions with the USSR. The Berlin Crisis of 1948–1949 and the subsequent construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 became symbols of the division of Germany — and of Europe as a whole — into U.S. and Soviet spheres of influence. Despite these challenges, West Germany quickly evolved into an economically prosperous and politically stable country, one of Washington’s key allies in Europe.

The construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 became a symbol of the division of Germany — and all of Europe — into U.S. and Soviet spheres of influence

But American foreign policy in the postwar period was not limited to the reconstruction of defeated countries. U.S. authorities were deeply concerned about the possibility of communism spreading into Western Europe — particularly Italy and France, where communist parties enjoyed broad popular support that made them contenders in democratic elections.

In response, the United States began actively backing anti-communist parties and movements, conducting large-scale propaganda campaigns, and exerting economic pressure. The postwar reforms in Germany and Japan were rare success stories, while efforts to contain communism elsewhere often resulted in armed conflict and political instability.

The CIA against communism

The U.S. regime-change strategy evolved over the course of the Cold War. As the nuclear powers vied for dominance, hot conflicts like the Korean and Vietnam wars were fraught with the risk of escalation — especially in Korea, where there was a real risk of the fighting developing into a nuclear war. Aware of these dangers, Washington increasingly sought to avoid overt interventions and relied more heavily on covert operations by intelligence agencies — primarily the CIA — that were aimed at supporting loyal regimes and removing potential allies of the socialist bloc.

One of the first examples of the new strategy was the 1953 coup in Iran. Tehran’s nationalization of the domestic oil industry had angered Britain, and the U.S. backed its British allies. The CIA, together with MI6, launched Operation Ajax, which deployed propaganda, orchestrated protests, and obtained support from the military in order to secure the ouster of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was restored to power and ruled the country for the next 26 years. Although the operation ensured the West’s short-term control, it fueled anti-Israeli and anti-American sentiment in Iran, which later played a role in the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

In 1954, the U.S. carried out a similar operation in Guatemala. President Jacobo Árbenz had initiated land reform that affected the interests of the American corporation United Fruit. Fearing the rise of leftist movements, the CIA launched Operation PBSuccess, which involved funding armed groups, spreading propaganda, and creating disinformation. As a result, Árbenz resigned, and a military junta seized power. The reforms were reversed, and a long civil war began, claiming thousands of lives and destabilizing the country for decades.

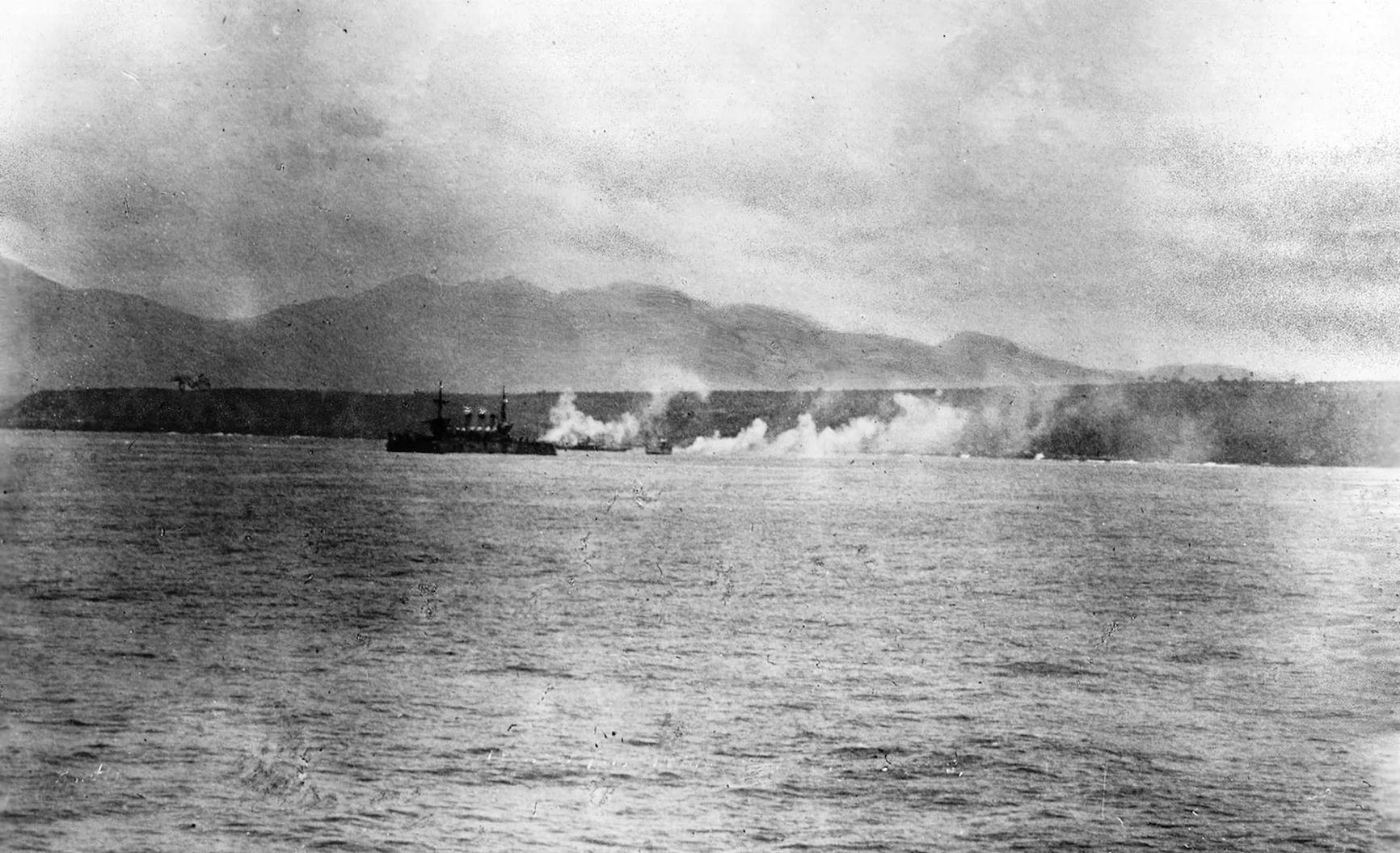

Another high-profile episode was U.S. support for the 1973 military coup in Chile. President Salvador Allende, who came to power through democratic elections, began nationalizing key industries, drawing Washington’s ire. The CIA organized an information campaign against Chile’s leadership and imposed an economic blockade on the country.

On September 11, 1973, a military coup took place. Allende died during the takeover, and General Augusto Pinochet came to power, and his dictatorial regime carried out mass repressions. Despite official claims of fighting communism, U.S. actions drew international condemnation.

Covert operations allowed the United States to avoid direct confrontation with the USSR, but they often led to regional destabilization and increased distrust of American policy, drawing condemnation from the international community

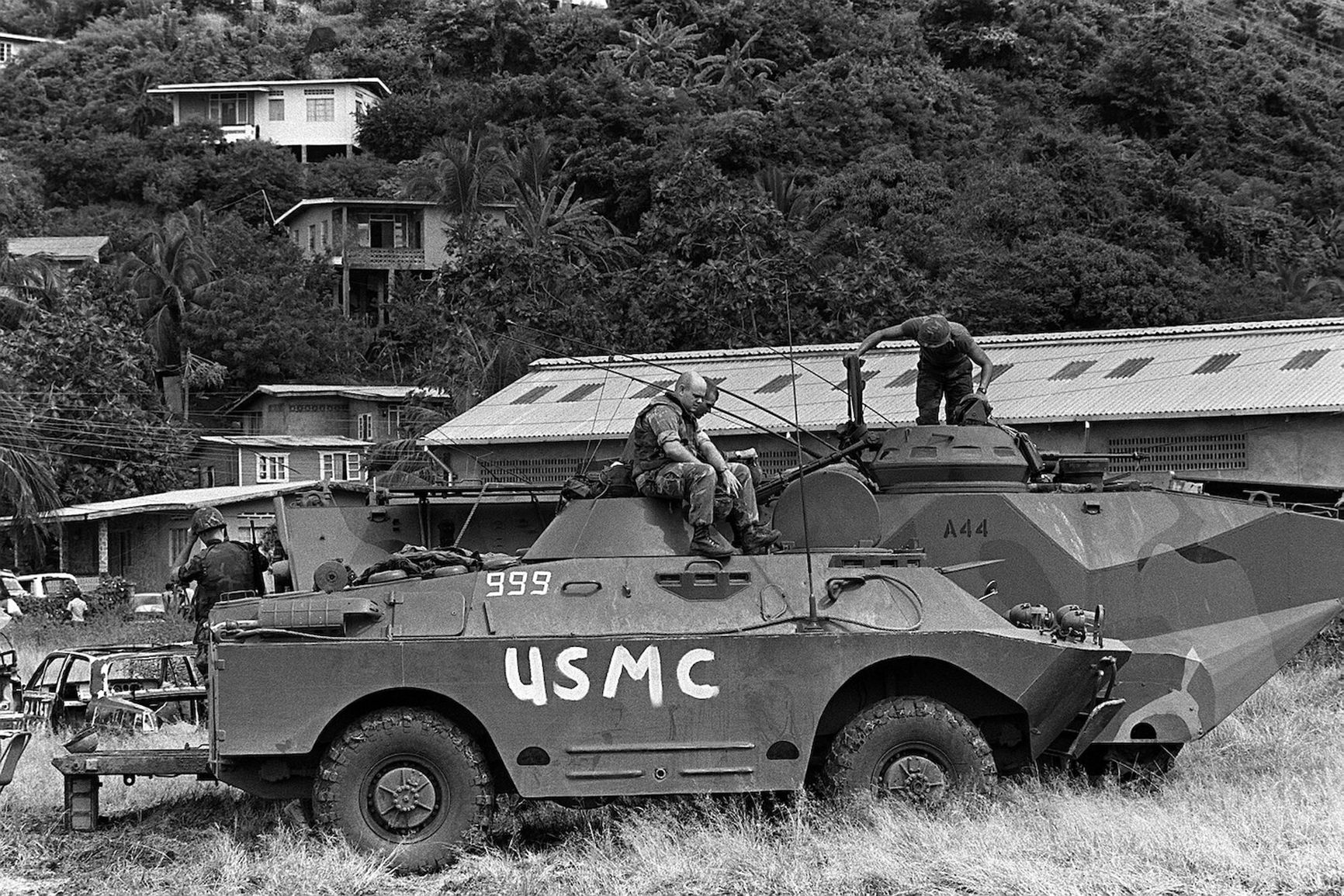

In 1983, following the assassination of Grenadian Prime Minister Maurice Bishop and the establishment of a military dictatorship in the country, the U.S. launched Operation Urgent Fury under the pretext that it was protecting American citizens and restoring democracy. Despite popular support for the operation among Grenadians, the international community condemned Washington for violating another country’s sovereignty. Grenada became a symbol of a “small, victorious war” — a successful yet controversial example of regime change in a country that posed no immediate threat to the United States.

Operation Just Cause followed in Panama in 1989. General Manuel Noriega, a former collaborator with U.S. intelligence services, had become an inconvenient ally and was accused of human rights violations and ties to drug cartels. After a short but intense campaign, Noriega was overthrown and arrested. However, the level of physical destruction and the high number of civilian casualties sparked serious criticism. Although the operation was declared a military success, questions about its legitimacy remained unresolved.

Easy to win, hard to control

After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the USSR, the U.S. emerged as the world’s sole global superpower, enjoying overwhelming military and political dominance. In Washington, the moment was seen as an opportunity to reinforce a “new world order” by overthrowing dictatorial regimes and promoting democratic values. However, the experience of interventions in the 1980s and 1990s showed that even with clear military superiority, achieving stable political outcomes could be an extremely difficult task.

The experience of U.S. interventions in the 1980s and 1990s showed that even with clear military superiority, achieving stable political outcomes could be extremely difficult

In the early 1990s, the U.S. sought to use military force as part of a humanitarian mission in Somalia. Initially aimed at delivering food aid to a population suffering from famine, the operation quickly escalated into armed clashes with local militias. The climax came with the 1993 Black Hawk Down Incident in Mogadishu, in which 18 American soldiers were killed and another 73 wounded. Public outrage led to the rapid withdrawal of troops, and the intervention in Somalia demonstrated how risky such campaigns can be without a clear political strategy or a deep understanding of local dynamics.

Another example of intervention during this period was the 1994 Operation Uphold Democracy in Haiti. Faced with the threat of a military invasion, the junta that had taken power after a coup backed down, allowing American forces to enter the country without resistance. The legitimately elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was restored to office, but the lack of structural reforms led to continued political instability. The experience in Haiti once again underscored that the forcible removal of a regime does not in itself lead to sustainable democratization.

However, the turning point for American foreign policy came with the 1999 operation in Kosovo. For the first time since the Cold War, the United States and its NATO allies launched a large-scale military campaign in Europe — in a region that had previously been within the Soviet sphere of influence. The operation was conducted without a UN mandate and was accompanied by serious legal and political controversy.

The official goal was to prevent a humanitarian catastrophe and ethnic cleansing, but critics pointed to violations of international law and the essentially unilateral nature of U.S. actions. Kosovo became a symbol of a new era: humanitarian concerns began to be used to legitimize armed intervention, and the line between protecting civilian populations and pursuing one’s own geopolitical interests was increasingly blurred.

Turning point: Iraq and Afghanistan

After the al-Qaeda terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, U.S. foreign policy experienced a radical shift. The United States declared a “war on terror,” which led to major interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq and became a watershed moment in global politics.

The Taliban regime in Afghanistan was accused of harboring al-Qaeda leaders responsible for the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, and in October 2001, the United States and its allies launched Operation Enduring Freedom. The Taliban were quickly overthrown, and power was transferred to a new pro-Western government led by Hamid Karzai. But the seeming success was followed by a protracted conflict. Despite extensive U.S. support, the Afghan government proved weak and corrupt, allowing Taliban fighters to gradually regain influence. The war dragged on for two decades, becoming the longest in U.S. history and resulting in heavy casualties, high economic costs, and growing anti-American sentiment around the world.

In 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq after accusing Saddam Hussein’s regime of developing weapons of mass destruction and harboring ties to terrorism. These claims were later disproven. Nevertheless, under the banner of combating a security threat, the U.S. overthrew Hussein and captured Baghdad. But instead of bringing stability, the country quickly descended into chaos.

Mistakes by the U.S. administration — particularly the dissolution of the Iraqi army and the ban on former Ba’athParty members’ participation in the new government — triggered a surge in violence and created the conditions for civil war. As state institutions collapsed, religious and ethnic tensions intensified, and numerous armed groups including ISIS emerged.

After the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, religious and ethnic conflicts deepened, and numerous armed groups appeared, including ISIS

The Iraq campaign severely damaged America’s image as a defender of democracy. At the same time, skepticism within American society toward direct interventions and regime-change policies continued to grow.

Lessons of intervention

Further doubts arose in the wake of the Arab Spring — particularly due to developments in Libya, Egypt, and Syria, where outside support for democratic change led to volatile and often disastrous outcomes. In Libya in 2011, the U.S. took on a supporting role, backing France and the UK in a military campaign against Muammar Gaddafi’s dictatorship. Although the regime was overthrown, the country soon descended into chaos and civil war.

A similar pattern unfolded in Syria, where Washington offered limited backing to opposition groups while regional and European powers took the lead. These interventions once again cast doubt on the effectiveness of foreign involvement in the absence of a clear post-conflict plan, and it exposed the limits of the American approach to democracy promotion.

In response, Washington began to pull back from direct interventions. The withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 and the scaling down of operations in Syria symbolized this strategic retreat. Today, the U.S. increasingly leans on diplomacy and economic pressure, opting to support allies from a distance rather than intervening directly — seeking to apply the lessons of the past while still asserting its role as a global leader.