Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa’s latest feature, Two Prosecutors, has been included in the competition of the Cannes Film Festival, which will be held in May. A fresh, sobering take on the era of Soviet totalitarianism, the Russian-language film stars Russian actors who fled their homeland amid its ongoing invasion of Ukraine. As critic Andrei Arkhangelsky writes, culture must resist Putinism, even if the struggle may at times seem futile.

The boredom of repression

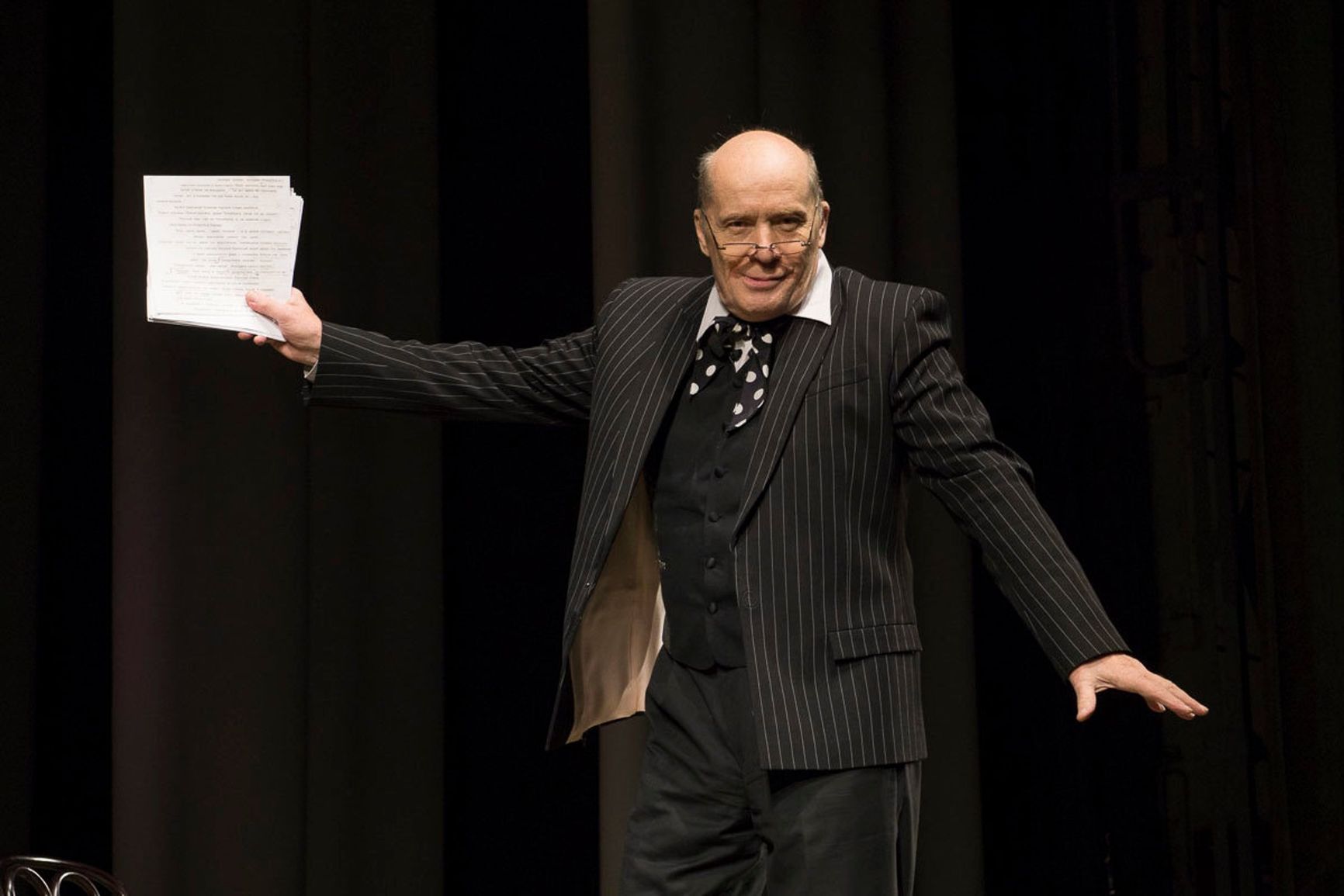

A joint production between France, the Netherlands, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania, Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa’s Two Prosecutors was nevertheless filmed in the Russian language with a cast prominently featuring Russian actors: Alexander Filippenko, Anatoly Bely, and Alexander Kuznetsov — all of whom have spoken out against the invasion of Ukraine. The story is set during the time of Stalin’s purges and explores the roots of violence in a totalitarian society.

“It’s time to look the Soviet monster straight in the eye. To defeat it, we must understand it,” Loznitsa said of his new movie. We ought to look for the roots of the modern-day neo-Soviet violence and work with totalitarian trauma — such is the message of both the filmmaker and the Cannes Film Festival, which included his oeuvre in the main competition. And yet for many in Russia, the tragedies of Soviet history have long since become old news — subjects not of intrigue, but of boredom. Before it started spewing curses at its enemies, Putin’s propaganda machine worked quietly, and since the 2000s, the Russian film industry has sought to make the tragedy of repression mundane — or, even worse, to paint it as a “great, if tragic, time,” equalizing greatness and crime. Hundreds of pedestrian TV shows have done their job: scenes of torture and firing squad executions have become a cliche. They no longer make an impression.

Since the 2000s, the Russian film industry has sought to make the tragedy of repression mundane

Loznitsa deliberately calls out this fatigue, revisiting the subject in the new context of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and of the tightening repression inside Russia itself. The filmmaker’s intention is clear from the selection of the literary source for his on-screen work: Georgy Demidov’s novel of the same name. Set in 1937, the literary version follows a young prosecutor on a quest to resist lawlessness as he eventually reaches out to Soviet Prosecutor General Andrei Vyshinsky. In the end, the protagonist is sent to a labor camp to meet his death in a cesspool.

Georgy Demidov’s remarkable writing is paralleled only by his real-life biography. A physicist and a student of Lev Landau, he too was sent to the Kolyma camps for 13 years — a grueling experience that is reflected in short stories and novels about life in the Gulag. Demidov’s uncompromising, hard-hitting prose puts him in the same cohort as Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Varlam Shalamov. At times, his journalistic style resembles perestroika-era magazines, but the similarity is deceptive: Demidov wrote in the 1950s-1970s, even if not a single line was published during the author’s lifetime. Demidov opens his novel by comparing 1937 to a deadly virus that infects everyone around it, and it ends like this: “In one of the barracks…guards began to discover stew with the remains of human bones. At the same time, daily checks showed that the entire roster of the camp was in place. Cannibalism was thus ruled out. They must have been eating cadavers.”

Written in 1969, the novel seems prophetic today. On the one hand, it evokes Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony,” a short story that forms the Penalties collection with his novellas “The Judgment” and “The Metamorphosis,” and on the other hand, parallels can be drawn with much later works. What Vladimir Sorokin approaches as grotesque in “The Norm” (1979) Demidov treats as realism:

“Under the window, if only it deserved that name, a man was sitting on a wall-mounted iron seat. His elbow rested on a similar table, also mounted on the wall with an iron bracket. He was tall, slightly stooped, and terribly thin. His clothes were dirty and as if chewed up, hanging on him like on a hanger.”

It’s as if Loznitsa is reminding the entire Russian cinema about the 2000s, where the conversation with the audience should have started: not with the sweet Children of Arbat (2004), where interrogation scenes are interspersed with pictures of “simple human happiness,” but with post-Soviet society repenting for its past crimes. The filmmaker is trying to restart the history of Russian-language cinema with a clean slate, so that the words “Stalin’s Great Terror” would not induce boredom in viewers.

The Cannes competition program is also a kind of art in itself. The very selection of films for the competition carries a different message each year, but one motif is recurrent: the jury defends the artist’s right to complexity, even in wartime. War simplifies everything and requires one to take a side, to pick one color. This presents a dilemma for the artist. Can they insist on their individual position — on personal complexity — in such circumstances?

A Don Quixote of the movies

Two Prosecutors is Sergei Loznitsa’s first feature film in seven years. His latest before the current endeavor, the black comedy Donbass, won the Un Certain Regard award at Cannes in 2018 “for its poignant look at the war in Ukraine.” In February 2022, Loznitsa quit the European Film Academy (EFA) in protest over its weak response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The next day, the academy called for a boycott of Russian movies. However, Loznitsa condemned the boycott: “Many of my friends and colleagues, Russian filmmakers, have spoken out against this insane war.” Shortly thereafter, he was expelled from the Ukrainian Film Academy.

Loznitsa insists on his cosmopolitanism but calls himself a Ukrainian director.

In his actions, he resembles Don Quixote, defending universal ideals and principles that are unattainable even in peacetime — let alone during a war. His gestures may appear deliberately scandalous, but Loznitsa is not one of those people. He was making movies and warning about the return of Soviet totalitarianism long before the subject became popular. He has dedicated almost all of his work, especially his documentaries, to this topic, one way or another: to the problems of short memory and irresponsibility. What does Loznitsa stand for today? For the artist’s right to complexity and individuality, even with a clear understanding of good and evil. Isn’t that utopian?

The art of guilt

In the new reality, the participation of Russian actors in any movie is bound to overshadow its plot or quality. Many Russian actors, filmmakers, and producers were involved in making movies about the Soviet Army or secret services before 2022, assuming it was “just a job.”

In the new reality, the participation of Russian actors in any movie is bound to overshadow its plot or quality

In retrospect, it becomes obvious that such projects were bringing the war closer. In April, Volodymyr Zelensky imposed sanctions against openly pro-invasion Russian cultural figures, whose stance leaves no room for interpretation. But what about those who chose silence? Those who have not made their voices heard? Those who still cling to the hope that culture can exist outside the realm of politics? The movie industry (both Russian and global) is a glasshouse: throw a stone at a colleague, and shattered shards will inevitably hit you. There are actors and directors who “had an epiphany” only after the war began. Can they be trusted?

The émigré actors’ sincerity is easy to check: just look at what artists like Two Prosecutors‘ lead Alexander Kuznetsov sacrificed by leaving Russia. An actor’s career is short, and emigration is a sure way to kill it. A Russian actor abroad can hardly count on winning the love of millions. Such a gesture deserves appreciation at the very least. The departure from Russia of the great Soviet actor Alexander Phillipenko in November 2022 at the age of 77 is also a powerful statement.

Besides, the Kremlin is now considering a program to return “prodigal sons and daughters” who are not guilty of particularly serious transgressions. A kind of “repentance” procedure is in the works. A Verstka source among the authorities warns that the relaxation will not affect journalists or political activists and is designed specifically for creative professionals, primarily popular actors and comedians like Ivan Urgant. The Kremlin appears to lack talent after all. Does that mean the departure of thousands of cultural figures from Russia had an impact on the regime?

In the eyes of the West, the Russian language seems to share the guilt with the Russian people, and this guilt is the sword of Damocles hanging over every Russian or Russian-speaking artist. As archaic as it may seem to the “citizens of the world,” as artists often like to define themselves, the stigma is a given for decades to come.

You can’t just “get over it.” It is something Russians will have to live with. We must accept that the outside perception of all things Russian will be filtered through the prism of the Russian state’s crimes. It is naive to demand indulgences for culture, as the plight of artists is unimportant against the backdrop of yet another deadly Russian strike on Ukraine.

A war of meanings

Does cultural resistance even make sense in wartime? In the first months of the invasion, art seemed to have irrevocably lost the battle against the totalitarian state. But today there is another argument: if Putinism as a phenomenon and as a threat to the world is going to be with us for a long time to come, then the fight against it will also be long, making cultural resistance, the struggle at the level of meanings, genuinely important. In the 1960s-1980s in the USSR, the language of freedom eventually overcame the language of totalitarianism. Assuming that opposition to the new totalitarianism will be a marathon, not a sprint, logic dictates that we need to get as many people on our side as possible.

Confronting the new totalitarianism will be a marathon, not a sprint

At the beginning of the full-scale war, Mikhail Khodorkovsky formulated a maxim that sadly never gained popularity: “It doesn’t matter what you did before 2022. What matters is what you are doing now.” It is a sound strategy — at least for wartime — because it increases rather than decreases the number of potential allies. And this is exactly the approach that ought to be applied to cultural figures leaving Russia after 2022. We live in a world of symbolic capital, and here, too, the strength is in numbers. The fewer talented people the Putin regime has, the better; that seems to be a concise but actionable formula for the future.